It’s fashion. It’s theatre. It’s sexuality. It’s politics… It’s the art of drag. The art of drag has challenged social norms and a prejudiced society while providing us with super lively and colourful entertainment. With an extensive and complex history, drag is much more than meets the eye. Sure, it’s the wigs, the extravagant make-up, the brilliantly planned outfits, the sequins, sparkles and the high heels, but, above all, it’s an art form.

Drag has probably existed from the moment humans decided to put on clothes—some caveman decided it’d be fun to put on his sister’s sheepskin cape and do a dance for the family [although I’m pretty sure men and women basically wore the same clothes for most of history]. In Ancient Egypt, Cleopatra and other queens were known to dress as a men to assert dominance and power in order to gain the throne, and men always took on female roles in Greek tragedies. Drag [as drag in name] starts in the Elizabethan era and we can thank the church [I’ll wait for you to finish giggling]. Ok, so there wasn’t a Pope who declared, “Thou shalt dress in garments from the opposite gender then go forth and busteth a move to Donna Summer records.” It’s more an indirect link. Five hundred years ago, the church was the authority, and they were quite good at imposing [their] principles on the people [stuff like absolving sins for cash payments]. One such rule was the banning women from the stage [they also weren’t allowed to vote or own property but we’ll save that story for another day]. WIth women at home rearing children, who would Shakespeare get play Lady Macbeth and Juliet? Young men, of course… and it is here that the term drag likely originated here as a form of slang meant to describe men wearing women’s clothes because their dresses would drag on the floor [genius]. From there, drag showed up in Japan as part of their Kabuki theatre, where female impersonators wearing intricate makeup would sing in falsetto voices, and Baroque operas also included examples of drag.

Drag is not just entertainment—it’s culture and its journey became political. Twentieth century drag came to the forefront with the emergence of Vaudeville—travelling shows featuring magicians, acrobats, comedians, jugglers, singers, and dancers. Female impersonation fit in perfectly with these live shows and from there, Julian Eltinge, the world’s first famous drag queen emerged. So famous, that in 1904 he made his Broadway debut in Mr. Wix of Wickham and eventually surpassed Charlie Chaplin as the highest paid actor in Hollywood. His ability to embody a woman was so convincing that when he removed his wig at the end of each performance, there were often cries of disbelief from the audience.

During WW1, The Dumbells [a name taken from the Third Division’s emblem—a red dumbbell that signified strength] were formed to raise the morale of Canadian troops on the front lines. The Dumbells performed wherever the troops were and their shows would include patriotic songs, dark comedy, and a taste of drag, giving the men their first peep at a lady in a very long time—which was great fun, even if it wasn’t a real lady. Between the wars, society changed and the end of the second world war was accompanied by the ‘rise of masculinity,’ and the public started to disdain everything that was non-normative behaviours—aka a more conservative society.

Enter the Hollywood’s Hays Code. By 1930, Hollywood had a very bad reputation and the general public viewed ‘movie people’ as morally questionable [probably a fair assessment] which was bad for business. In an attempt to clean house, the industry consulted with religious groups, and political organizations [what could possibly go wrong here] to create a set of rules.

The implementation of the code in 1934, drove drag underground. The Production code outlined what was or wasn’t acceptable in film production—profanity, sexual relations outside marriage and any sexual act including suggestion of same sex relations were deemed immoral. Despite there being a misconception that all drag performers are part of the LGBTQ+ community, those two communities were closely linked, so impersonating the opposite gender was also made taboo. While some took drag behind closed doors, others found outlaw bars where being queer was celebrated. Known as the “Pansy Craze”, it was in these scenarios that drag performers such as Ray Bourbon, Bryz Fletcher, Jean Malin and many others rose to fame.

With the heavy policing and stigmatization of drag culture in North America, Canada made changes to the Criminal Code in 1948 and the persecution of the LGBTQ+ and drag community came under “acts of gross indecency”. Carte blanche for the police who took their harassment to LGBTQ+ friendly establishments, many of whom allowed drag performances. Unfortunately, this reaction wasn’t unique to Canada. New York state went as far as enforcing anti-cross-dressing laws which made dressing in drag just as illegal as stealing a car. Police raids on gay clubs in New York City led to a series of riots organized by drag queens in 1969. The Stonewall Riots [named after the club where they started] are considered a landmark moment in LGBTQ+ history. Only in the 70’s, did Canada’s Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau finally declare [what should be a universal law] “There’s no place for the State in the bedrooms of the nation”. The first gay rights march took place in Ottawa that same year and we saw a resurface of drag soon after that.

The Queen, a 1968 movie was proof that drag was regaining the spotlight. The documentary is narrated by Jack Doroshow, a 24-year-old man living in New York who works as a drag queen named Flawless Sabrina, and depicts the drag queens participating in the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Contest. Through the 70s we saw artists like David Bowie breaking gender stereotypes, Tim Curry dragged out as Frank-N-Furter in 1975’s Rocky Horror Picture and even drag queen Lori Shannon enter our living rooms in his recurring role on the popular sitcom All in the Family.

Slowly, drag bled into the mainstream and started appearing everywhere—movies like Pink Flaming starring the contra-culture icon Divine or Paris is Burning which showed the more glamourous side of drag. Boy George, Dead or Alive’s Pete Burns, Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie, Tom Hanks in Bosom Buddies, Robin Williams as Mrs. Doubtfire, The Birdcage, the list is long and fun. in the 80’s and 90’s, drag had become pop culture.

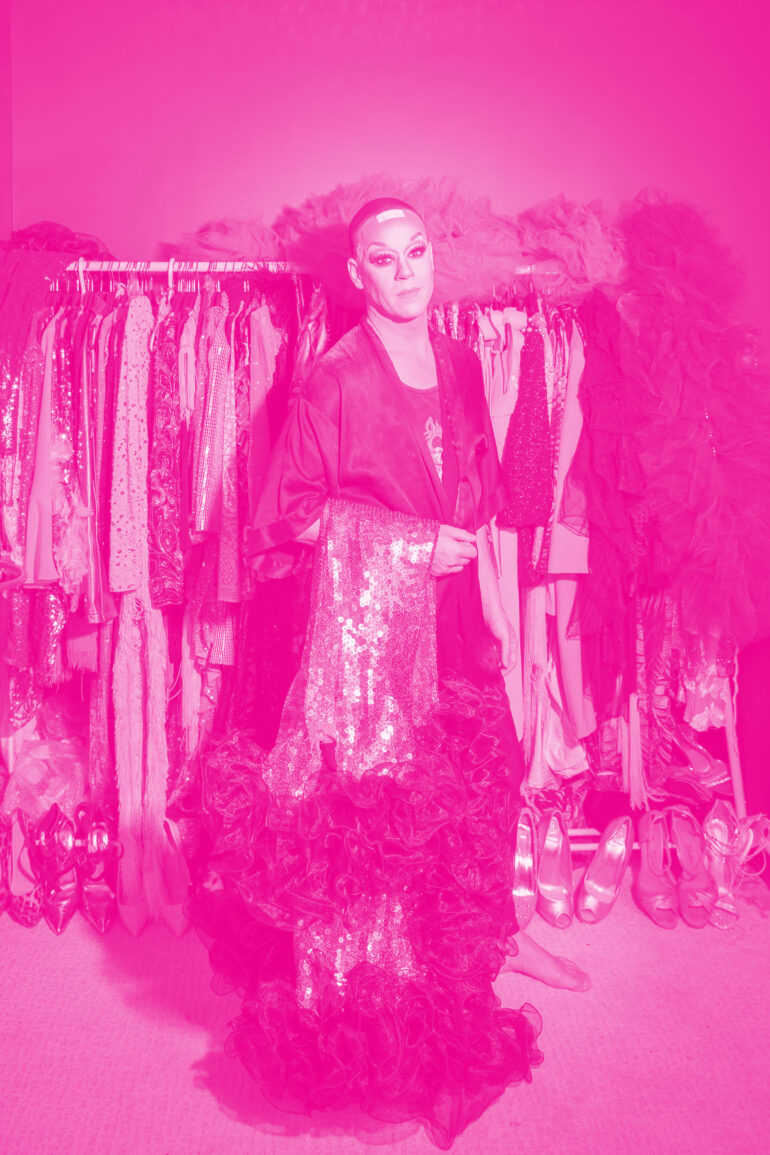

I am very aware that there’s a notable inauthenticity to a straight woman writing an article about drag. Yes I did a lot of reading and yes I’ve enjoyed a few shows, but all I am able to do is run through a brief history of it. This wasn’t enough. vJason opened the door to his drag-room, where Jezebel Bardot comes to life—a persona inspired by Bridgit Bardot, the symbol of women’s liberation and beauty in 1960’s France. We talked, took photos and now the rest of the show is in Jezebel’s words.

I am very aware that there’s something unauthentic about a straight woman writing an article about the art of drag. Yes I did a lot of reading and yes I’ve enjoyed a few shows, but all I am able to put down on paper are some historic facts. Like you, I wanted more. Jason opened the door to his drag-room, where Jezebel Bardot comes to life—a persona inspired by Bridgit Bardot, the symbol of women’s liberation and beauty in 1960’s France. We talked, took photos and we end this article with Jezebel’s words.

My style of drag, and drag in general, is the art of fooling the eye. Drag is an illusion. You are capturing and you are taking people into believing they are watching something that is not really going on. Which is a man, in a dress, dancing like a woman. Although I am clearly a man, I am still able, for the duration of a number, to really capture people and make them believe they are watching something that is not really reality. Jezebel, if you look at the biblical figure, although she was a very negative and bad figure in the bible, historically, she really fooled a lot of people into believing in really bad stuff. So, there’s a parallel there, between the biblical Jezebel and Jezebel in the sense of the art of drag. You are fooled to believe there is something going on that is not really true.

I’m not surprised that drag happened in my life. It was not something that I actively thought out. It kind of happened by accident. Before doing drag, I had a career in gymnastics. A long supporting career, I was on the national team for gymnastics. I really wanted to get into Cirque du Soleil—that was a big goal of mine. After injuries and my perspective of life changed, not wanting to live out of a suitcase kind of thing, I decided to go for a more stable job. My career in gymnastics ended and then I kind let things go for a while, but I was always a very creative person. I was always a gay man, a little bit feminine, I always loved pretty costumes and things like that—the show, the lighting, the fantasy of it all. When I moved to Toronto, I had an opportunity through the gay volleyball league to dress up in drag and make people laugh as an amateur kind of show during one of our tournaments.

I discovered in that moment the power of drag—to bring people together, to heal and to talk about problems in a funny way. I realized that drag, for me, could become my own version of Cirque du Soleil, the career that I never got to have. I get to have elements of acrobatics in my drag, I get to do make-up and I get to be under stage lights, which is something that I’ve always fantasized about with Cirque du Soleil. Drag has become a second career. I have a very established career as an educator, but I’ve always kept drag because it was not only my creative outlet and something that I love to do, but it also became a small business. It’s a way to express myself, to blow off some steam, to get rid of some of the stress during the week, and I get to live my life as the show-business person that I never really got… but I got to have it in this form which is amazing.

This is something that comes from another part of my life—I’ve learnt two separate things. In my previous life as a gymnast, I was training 30 hours a week. No one could talk to me without talking about gymnastics. It was such a big part of my life that everyone would even call me gymnast. It was so attached to my identity—I was coaching gymnastics, I was training and making an income. Then I went to university and completed a degree in Sports Psychology—again attached to gymnastics. I had dreams of being part of the Cirque du Soleil but I injured myself. Now it wasn’t just Jason the gymnast that was not good. My identity was so attached to being a gymnast that my whole life crumbled because I didn’t have anything else to rely on. When I started doing drag and playing with my new identity as Jezebel, it was important for me to differentiate between the two. For example, if I’m having a great night as Jezebel, I get to celebrate that success in both Jason and Jezebel. But if I’m having a bad night as Jezebel, I can put the wig and the costumes away for a while and have my whole other life where I have other interests and things that I’m good at, and can distract myself with. I’ve learned to compartmentalize my drag and I find it to be the healthy way to approach theatre and drag for myself.

I like to take songs that bring an emotion out of people or brings them back to a memory, instead of something that is popular. I did a song for Mother’s Day, Good Mother from Jann Arden, which you wouldn’t typically see in drag because it’s not upbeat. I did it because my mom loved that song, I love that song and it fits the theme. I didn’t realize that could trigger some emotions in some people who maybe don’t have a good relationship with their mother or who lost their mother. And I had someone come up to me and say, “Thank you for doing that song. Mother’s Day is always hard for me, although I am emotional and I don’t usually listen to this song at home because it brings bad memories, seeing you having fun performing it forced me to listen to it again and live a good memory.”

You have to have a good group of friends who support you—on and off stage. In the role of Drag Queen you will often find yourself in the centre of friendship groups. You are the centre of fun. On Friday, I used to finish work, go home, quick shower, a bit to eat and would start getting ready for my show. My friends wouldn’t even have to message, they would show up with drinks at my house, we would have drinks as I get ready—you become the mother figure where everybody gathers. You are the centre of attention as you are doing your make-up. Then 11 o’clock hits, we’re out of the condo and off to the bar. People give you shots, money and take pictures. Again, you are the centre of attention. Then, you go on stage and do your performance. Again, validation. What happens is that when 2 o’clock hits, the bar closes and now you are not only alone, but also exhausted. You can easily fall into a trap of—look at this fun, validation. I’m the centre of attention, I’m making a difference, making people excited about things and all of a sudden, very quickly… you are alone. If you do drag and you can say, “Well I am alone now but that’s great because I had a really good time and I performed well,” that’s fine. But if you are doing drag because all you care about is attention, attention, attention, that moment of silence and the moments of loneliness are very difficult.

WORDS: INËS CARPINTEIRO

PHOTOS: RAMON VASCONCELOS

You must be logged in to post a comment.