If you’re someone I think is cool, I want you in the magazine, which means I’ve probably jotted down a question or two that I plan to ask you when we finally meet. [Iggy Pop, I’m coming for you]. Many of those questions are ridiculous, but I write them down anyway.

The Sheepdogs are one of those bands. I put them on my “cool list” after watching their Edgefest 2012 performance. The band was tight, sending good vibes to everyone within earshot. Bluesy and upbeat, southern feel-good rock ‘n’ roll… the kind of music you had blaring from the car stereo during that road-trip when the cop pulled you over for speeding and instead of giving you a ticket he just smiled, gave an understanding nod and sent you on your way after saying one word, “Sheepdogs.” I was hooked.

At some point after that concert, I crafted my question and put it away until the opportunity to interview a Sheepdog or two presented itself. This year, the ‘Dogs released a pair of stellar albums—Live at Lee’s followed by Outta Sight, they announced a fall tour and then the stars aligned. I reached out to long-time e-penpal and music publicist, Cristina Fernandes in an attempt to sit her down long enough to chat about doing something for the magazine [cool chick… see paragraph one]. Unfortunately for us Cristina is a busy person. Fortunately for us Cristina is busy being a publicist. During our convo, The Sheepdogs came up, and it turns out they are her clients. Shortly after, an email came in—“Ewan and Ryan are a go. Interview is noon on Wednesday. Ryan thought it’d be fun to do the shoot at a sports bars in Little Portugal.” Noted.

Thirty-six hours to prepare. I had one question and an eager photographer… what could possibly go wrong? I told everyone to meet at the Nossa Casa Sports Cafe on Dundas Street—everyone except the owners of Nossa Casa. No big. I showed up at 10am and spoke with the owner, who politely declined my request. “Thanks, but we’re not interested.”

“Wait, what? We only need an hour and won’t be in anyone’s way… The band requested a place like yours… We’ll be interviewing a couple of freakin’ Sheepdogs…”

“No. No. No.”

With the clock hands getting closer to noon, I downed my fourth espresso and thought, “What would the Sheepdogs do?” They’d appeal to the “every man” sensibility. “You know,” I said, “the boys had actually suggested another bar up the street. I told them Nossa Casa was a better spot because I have family who come here—my cousin Mario, his son Armand, even my son had been here to watch a few soccer games.”

With that, he broke, “If your family comes here, and they recommended us, I don’t want to let them down. Do your thing.”

I exhaled and ordered a beer to hopefully reverse the effects the caffeine was having on my nerves, then looked up at the clock—11:41. I had 19 minutes to chill out before Ewan and Ryan showed up. I took a sip and looked over my questions.“Fuck it,” I thought, “I’m leading with the ridiculous…”

Luso Life: Okay. So I’ve been holding this question for a long time, way before there was even a thought of an interview. You were the first unsigned band to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone, how does that compare to being the first signed band on the cover of Luso Life?

Ewan Currie: They’re both honours. It took a long time to get here. [laughs]

It’s a stupid question, but I needed to ask it. That was a super cool thing, though. Obviously, you guys have talked a lot about the Rolling Stone thing but I heard you were the only Canadian band that entered.

Ryan Gullen: It wasn’t even something we entered. Somebody at Atlantic Records that had gotten a hold of our album and then put us in the pile. Then Rolling Stone and Atlantic picked ten or 14 bands, or whatever it was, so it was actually a surprise when we found out we were in that competition. It was sort of like, “Hey, are you interested in being a part of this?” It was completely out of the blue. It wasn’t something we entered, but we were the only Canadian band. We were very fortunate. We really got the Canadian community behind us to help with that.

So, Dua Lipa’s latest album is named Future Nostalgia… I can only assume it’s a nod to you guys?

Ewan: She’s a big fan of ours. [laughs] We took it from a sketch from an old TV show called Mr. Show—Bob Odenkirk and David Cross, so it’s a nod to that. The only thing I can think of is, aside from it’s just a phrase that’s out in the world, I think one of the guys that worked on that album is this guy Stephen [Kozmeniuk aka Koz]. We met him years ago, he was in a band called Boy that was a rock band, kind of in our style, and he’s now, a super writer/producer for the stars. He worked on that record. So I’m wondering if maybe he knew or he maybe had a hand in that. I don’t know.

Ryan: We also just joke that at some point, maybe she’s looked us up and seen that our record will come up, if you type it in. So maybe we get a few spins occasionally. One for every 10 million that she gets. [laughs]

There’s nothing wrong with that. While we’re talking about that genre, I couldn’t find it anywhere, but have The Sheepdogs ever been sampled? Do you know?

Ryan: I don’t think so. I mean, typically people are pretty good at clearing that stuff, so no. We’ve talked about that… how it would be great to get some samples rocking.

You guys are considered Canadian rock royalty by this point…

Ewan: Maybe princes or something. I would never dub myself Royalty.

You get lots of love here… you’ve played all over the world… outside of Canada, do you guys fill rooms of the same size?

Ewan: We’re more like rock ‘n’ roll peasants [laughs].

Ewan: It depends where we go… We’re going to the UK—we fly out tonight. So we’ll be playing rooms that are a little smaller [than we play in Canada]. We go to America and the UK and Europe—we’ve been building it up… to get it up to the same level.

Ryan: We’re a li ttle bit more of the rock ‘n’ roll working man, the working class. We’re out there pounding the pavement a little bit more. We’ve been able to continue to have the ball rolling in Canada, but for a lot of people in America and Europe, we are still a fairly unknown band. We have a very devout following in those places, but it still will continue to grow. We’ve been to Europe once this year, this will be our second trip to the UK. We’re going back because our shows in January sold out and we’re going back to do those same venues again—bigger venues, so we’re seeing growth, but we’re not rock ‘n’ roll royalty by any means. [laughs]

Does the world see you as Canadian or do they see you as American or do they just see you as music?

Ewan: I don’t know. We are Canadian, but I don’t think that really is first and foremost—we’re not always super conscious of singing about Canada. When we go to the UK and Europe, it’s like, we’re just a band from North America that plays American style rock and roll. In the States, we go down to the south and we play some of our licks, and they’re like, “Wow, you guys sound like you’re from down here, but I know you’re from Canada.” I don’t think people really care that much… if the music is good, it doesn’t really matter.

I remember when I’d go to Portugal in the 80s and 90s, the charts there were filled with stuff from everywhere—people were singing in whatever language and it was all accepted. Back in North America it was more like, “Hmm, we’ll let “La Bamba” in, but everything else should be in English.”

Ewan: There’s a real thing with rock ‘n’ roll, I think it’s really tied to the English language. People love it in all languages but for some reason it’s sort of tied to English. When you go to Spain or wherever, people go nuts, singing back to you. Even if they don’t speak English, they’ll sing lyrics back to you and kind of latch onto it. They don’t seem to produce a lot of their own rock ‘n’ roll bands over there, but they love the genre.

Ryan: It’s a funny thing… you’ll go to a country where you can’t even have a conversation with someone after the show but then they’re singing lyrics to new songs. That’s kind of the power of music, that people can discover music and learn the words but then have difficulty having a conversation. Obviously, when we go on those tours, we’re in a different country with a different language every single day. It’s a very bizarre thing.

You see some of the concerts out of Brazil, where you have 100,000 fans, and they don’t speak English but they’re all singing along with Queen or Megadeath.

Ewan: Yeah, that’s what’s great about music. It’s like the feeling of just hearing a melody or the rhythm—you don’t necessarily need to speak the language. I listen to a lot of Brazilian music from the 60s and 70s Tropicália era. That’s all in Portuguese. I don’t speak Portuguese but it sounds beautiful. I love the sound of it and it speaks to me just through the music.

So as a listener and a writer, you prioritize melody, or the lyrics?

Ewan: I prioritize melody. Like I said, I connect to music first—I get melodies and riffs stuck in my head. That’s why I enjoy listening to music that’s in different languages, whether it’s Portuguese or French or Italian. The melody is the thing that really connects to me. It’s not to say that lyrics aren’t important but to me, I really connected to the music. I think you can go a lot further with a strong melody and shaky word than the other way around. That’s just me.

Ryan: Often, the most ambiguous lyrics end up having more meaning to people than when they’re very like on the nose too. Ambiguity is a good thing in music. We’ve often talked about that universal lyric, but we’ll meet people and they’ll be like, “Oh, in this song, this lyric meant this to me.” And that’s cool.

Ewan: If someone asks me the meaning of something, I don’t care if they know the right meaning. I’d rather they just interpret it and have their own thing.

I like that music is a universal language because, like I said, when we go to Spain, and places where they don’t necessarily speak English, they’ll sing the riff. We played a show in Spain, they were singing one of the riffs of our songs back to us, as if it was a football anthem, like the soccer matches. That’s really cool and it just feels great to connect with somebody through something that doesn’t, you know?

Ryan: That’s a funny one because that happened twice on our European tour—at the first in Hondarribia, Spain and the last show in Paris. Both shows, at the end of the night, people were singing our song. You know how they do Seven Nation Army at football games now? They were doing that in the crowd and it was this amazing moment where it was like a universal thing that two neighbouring countries did kind of the same thing.

What song?

Ryan:”Nobody.” They were like, “da da da daaa.” [sings riff] A roomful of people doing that is pretty powerful.

Ewan: One other point about the words versus music is sometimes, someone will post a lyric as their Facebook status or as a tweet or whatever, and if you don’t know what the music is behind it, or the song—unless it’s a really good line—you think, what the hell is this? But if you know the line, it makes sense because it has that music. It just imbues it with a special flavour that writing on its own can’t do.

Do you have a favourite line you or somebody else has written?

Ewan: “The love you take Is equal to the love you make.” [laughs]

Ryan: After watching that Beatles doc, it’s so funny because you see, sort of to Ewan’s point, where it’s like something that ends up being profound can come from a very unprofound moment, and I often have wondered that about that line. It’s so incredibly profound. I do believe that’s one of the best lyrics but I have a feeling it could very easily have just been come up with on the spot. It’s quite possible it doesn’t have this deep-seated moment. A profound moment can come from essentially nothing. I think that’s one of the things that’s so interesting about that Beatles doc, or any music that’s being created, it’s not always created in these amazing circumstances where everyone in the room is like, “oh my god! There’s magic happening right now and we know this is gonna be something special.”

Ewan: I’ve thought of a good line. “Deacon Blues” by Steely Dan. “Learn to work the saxophone, I play just what I feel. Drink Scotch whiskey all night long and die behind the wheel.” The other line, “They call Alabama the Crimson Tide, call me Deacon Blues.” The [University of] Alabama football team, which he’s looking down his nose at them like they’re a bunch of hillbillies, have been given this grand name, the ‘Crimson Tide’, and he’s like, “I’m just some loser, so call me Deacon Blues.” It’s a good line.

Yeah it is. One of my favourite moments in the Beatles doc involves some magic happening—when Paul is writing “Get Back.” You’ve got George and Ringo, just watching Paul messing around on the bass. George is yawning and Ringo is wiping sleep from his eyes. Then the song starts to come together and you see George pick up the guitar to join in and Ringo starts to bang on his leg, and we watch the song magically come together. Does that type of thing happen with you guys, where you’re jamming in the studio, and everybody’s contributing, or do you come in and say, “there’s your parts, please play them the way I’ve asked you to?”

Ewan: It depends. Sometimes it is like, here’s your part… not that I write out sheet music or anything. Other times, it’s just a kernel of an idea and we jam it out. It is wild to see that happen in the movie, that it just happened so seemingly out of thin air, then it turns into their new number one hit… crazy. So yeah, sometimes it’s fully formed and other times, it’s just a skeleton of an idea. As a songwriter, sometimes you can see it all in your head or hear it all in your head. Other times, you can’t… you just have this piece, but then once you get the band around you turning it from an idea into this 3-D thing, you can start to envision it, once you hear it in the room. It’s weird, because sometimes you envision a song, and you’re like, “I know, it’s gonna be like this, and it’s gonna work out like this,” and then once you’re actually playing it, you’re just like, “I can’t make it sound like it does my head.” Then it becomes something else.

Ryan: I think what’s interesting about this record is because of the nature of making an album during the pandemic, we sort of would just get together and jam on ideas. It was a pretty unique way for us to make a record. Ewan would come in with ideas that he had demoed or worked on over the pandemic, and we’d all sit in the room, basically in a circle, and just try things out. Like he said, it might have been a fully formed idea and we would make suggestions, but other times, it would be literally us trying things out. We would go and record a little bit then listen back. Other records we’ve done, songs have taken shape over long periods of time, or have already been pre-formed and jammed, and when we would come into the studio we knew exactly what we were doing.

So, because Outta Sight was a pandemic album, did you have more time with it?

Ewan: Less time. We don’t all live nearby. Three of us live in the city, one guy is off in Saskatchewan, so time with all five of us in a room was limited. Also we ended up being discouraged from doing things together and congregating. Every now and again, we would have some reason to get together, so we would just book a couple of days in the studio, and just try to bang out songs.

Ryan: We didn’t have that much time, being separate.

Ewan: We were supposed to go to the States and do a proper two to three weeks and sink our teeth into making a whole record, but that was basically scheduled for April 2020… of course, you know, the border shutdown and everything else. Basically, you know what the pandemic was like. You’d make some plans and then the rules would change, and then those plans got screwed. We were just kind of desperate to do something that felt like we were accomplishing something. You can’t play shows, you’d plan to do a video project and then the government would be like, “actually, we’re not allowing this right now, because you can’t have these people together in a room.” We were just like, let’s just get in the studio and try to accomplish something. It worked out pretty well the first time we tried it, so we just kept going, and next thing you know we had eleven songs,

As a result, we didn’t over-think it. It was very basic… that workman mentality—come in, work on something, finish it, and then it eventually became the album. Our previous full-length record was a very different story, where it was actually longer. We’d try different things and it was more drawn out. With this, we’d focus on one thing, get it done, and then move on to the next thing,

Very cool that you were able to write a very uplifting rock album while the world was falling apart.

Ewan: When we started our band, we were both kind of miserable. I had a breakup when I was 19, so it was an end-of-the-world kind of vibe. Ryan got fired from his prestigious job at Blockbuster, ruining his career as a video store clerk…

Ryan: You really did me a favour.

Ewan: It was right at the start of summer, and summer was looking like a bummer. We started the band right around that time, and I was driving around in my car listening to Creedence, listening to the Kinks, listening to rock and roll music and just trying to cheer myself up. I really was using rock ‘n’ roll as a drug to make myself happy and to escape feeling like a bummed out dude. When you’re 19, you just think, “this is the end of the world, and nothing’s gonna get better.” I love rock ‘n’ roll as a sort of optimism. Even if your life sucks or your job sucks, Friday night rolls around, you got a bit of money in your pocket and you’re going to have a good time—whatever that is for you. For me, we would get together in the basement of our drummer Sam’s parents house. Jam, drink beers, and go out to a bar to see some music. I want the rock ‘n’ roll music that we make to be an escape. It’s always been that way and then the pandemic rolls around, and more than ever, it’s good for that. So it was a little bit of wishful thinking—I think we were always acutely aware that when this thing was over, we were going to try to put it in our rear-view and not think about it.

Ryan: I think everything about it was, even ourselves thinking about making music, we knew that whatever the end or the next part of the pandemic looked now—playing shows, putting out music, doing in person interviews instead of Zoom—all those things that we were so accustomed to, and never really stopped doing until the pandemic hit. A lot of what we were doing was, “we’re working on this now so that this can come out and we can have it.” It’s all looking forward to that as well, as everybody was at the time—hurry up we’re waiting for things to hopefully go back to normal.

Ewan: If you think about your favourite Beatles records, and I’ll use “Taxman”… it will reference Mr. Wilson, Mr. Heath and politicians of the day, but it’s not married to 1966 or whatever. It’s not like they’re only commenting about that. It might reflect the moods of that time, but they’re still universal enough that they can be attached to anytime. I think timelessness in music is the goal.

Absolutely. When I chatted with Ron Hawkins, he said he wished Lowest of the Low had recorded a very happy-go-lucky album, like Katrina and the Waves. Coming out of the pandemic, I think that would’ve been so fun.

Ryan: Yeah, that’s what’s been fun about the shows we’re doing now. We have those new songs that are good vibes and people are just so happy to be back. We’ve been fortunate to be the first shows back at a lot of places. In November we did four sold-out nights at Lee’s Palace in Toronto—that was the first weekend indoor shows were allowed in Toronto. So we got to do these four shows where it was everybody’s first indoor show and the energy was incredible. We had a recording and then we put out a live record [Live At Lees] from it because it was this incredible moment. We went to the UK in January and same thing. They’d just opened up, a lot of bands are cancelling their tours, and we decided to go anyway. Shows were very packed and people were just happy—for everyone, it was first shows back. Now, having just done the first leg of many, many shows we’re doing in North America, the East Coast of Canada and Quebec, same thing. People are just happy to be back, happy to get back to a regular way of life and back in a room. I think one of the strengths of rock music is that it is exponential. Being in a room full of people singing along to songs, feeling that energy, both for us onstage or us in the audience, is a great moment. That exponential experience, I think is what all of us were really missing, whether it was at a sporting event or in a bar with your friends, those are things that we took for granted. So, it’s been fun to be that first for a lot of people in that way.

Everyone knows that you wear all your influences on your sleeve. Do you feel that you’ve taken the baton from the old rockers and now have a sense of responsibility to keep great guitar rock alive with gen-whatever or is it not that deep?

Ewan: Responsibility? No, I don’t feel responsibly. I feel a bit of an honour. The last bunch of rock concerts I went to, the guys are all over seventy. There’s usually two original members at best. I saw Doobie Brothers and Bonnie Raitt this summer, those are my two concerts. They’re not going to be rocking for that much longer. The kids are more into like electronic music, hip hop and stuff, so it’s different. Going back to what Ryan said about the experiential thing, I think a great element of going to our concert is that it brings rock ‘n’ roll fans together. So you kind of find your like-minded people. It doesn’t have to necessarily be people, like, “I met my future husband at your show,” although that has happened, but just bringing all the rock ‘n’ roll people in that town together for one night is so cool because it’s not the most popular genre anymore. It’s a more of a niche. I love it because we love rock ‘n’ roll music. It’s like when you find a bar, in some city you’re not from, and you’re like, “This is my style and this is my type of music.” It’s like, yes, these are my people, everybody’s into the same thing—just a shared experience.

Ryan: It’s funny, I was out last night for a short while, I met somebody and we were both wearing a denim shirt that had embroidery on it. I said to him, “Nice shirt. I see we obviously shop at the same store.” And he’s like, “and I can guess we probably can talk a lot about music, based on how you look.” We didn’t even talk about music but we knew that based on how we both looked, we both like rock ‘n’ roll music. It was just kind of a funny thing. I think there’s something to be said about that. When you’re around like-minded people, it’s good. I think what’s interesting is that electronic music and hip hop are very popular, but we’re also at a time where it’s very easy to discover new types of music. Historically, you would have to go to a music store or have a friend’s cool, older brother that would turn you on to something. Whereas now you can go down these rabbit holes and discover things. Ewan and I went to high school during the Napster era, where we could start looking things up and downloading music. Obviously that’s not great for musicians but it’s great for discovering music, especially growing up in a small city with limited resources. On this last tour, the age range of people coming to our concerts are literally 70-year-olds and 15-year-olds. There was a show we did in Vermont and there were two people that had the underage wristbands on—they were probably 16 years old. It’s pretty amazing to see that, because I think there’s this thing where people can get into something—they don’t need to be force-fed, whatever is on the radio, which in a historical music model, was like, “You’re gonna like Third Eye Blind because Third Eye Blind is what’s on the radio, and it’s popular right now.” As a result, I think there are more avenues for bands to exist that are a little bit more niche. You don’t have to just chase whatever is popular… and one thing we’ve never done in our career is really chase what’s popular. We rode out all sorts of different waves and different things. So I think it’s interesting to discover that. So we’re just gonna continue doing what we’re doing, and people that are into it will discover and come into the fold.

A lot of people of my generation complain that new music sucks, and I constantly bring you guys [and others] to prove my point that great music is still being made. Do you fall into the “new music sucks” category?

Ewan: I think it’s just style. There are definitely bands that I hear and think this is cool, but they’re playing more of that 60s/70s style, which is what we aspire to. You know, stylistic difference.

So, to switch away from music, I love all your artwork and all of your photography—you guys seem to have a lot of fun with it—visually, your album covers seem to go outside of what your music sounds like. Like the cover for Outta Sight could’ve been one of those old K-Tel albums, full of 80s hits like “Elvira” by the Oak Ridge Boys and Steve Miller’s “Abracadabra.”

Ryan: I mean, all of our artwork, and all of our photos are all done by one guy, his name is Mat Dunlap. He’s originally from the East Coast. We met him there but he lives in Los Angeles now, and we’ve been working with him for the last 10 years on almost all of the stuff that we’ve done. We’re very involved in the conversations and he’s the guy that helps us. He’s like the extra member of our band in some capacity. He looks like us, he does all our photos…

Ewan: He’s very much a kindred spirit.

Ryan: Him and I do other things together as well, like videos and whatever. So yeah, we like to have a big hand in that. How you’re represented is very important.

Ewan: We’ll just hop on a Zoom and throw ideas at him, and he absorbs them like he’s being splattered by a paintball gun. Then he goes away and figures out how to make it actually happen. We have very similar sensibilities. He’s a big fan of not just old music, but also old design. We just loved a lot of those old vibes… and everything’s on the table, so it’s not just classic album covers… we love that sort of K-Tel, classic, silly stuff. You can see in some of our silly videos that we have those old infomercial vibes. We’re kind of pop culture nerds in a retro way, I guess.

Yeah. There’s a total sense of humour with you guys.

Ryan: We don’t like to take ourselves too seriously. I think that rock ‘n’ roll can be serious but we’re not in that mindset. We think it should be fun. And we’d like to have fun with it. We’re happy to sort of make fun of ourselves a little bit. We’re happy to make it fun because I think, in a world where a lot of things are serious, it’s nice to have that be the fun part.

Ewan: I did buy a black shirt today. I’m getting a little more serious.

I was wondering if Shamus has suggested adding a few more horns to your shows? Maybe add a New Orleans vibe?

Ewan: Well, the first song on the record has trumpet, trombone and two saxophones. Shamus is the trombonist, as always, Jim, our guitar player at the time, plays trumpet, and Sam and I play sax. Shamus can really play, the rest of us barely squeaked out a few notes that sounded okay in a, ‘works in a sloppy Rolling Stones kind of way.’

Best bar band ever.

Ewan: Absolutely. We’ve had a few different horn players play with us. I’d like to do some more. Horns are definitely always on the table. It’s tricky because you always want to make it work… you don’t want to just tack it on for the sake of tacking it on but I definitely think it’s something we’ll do in the future.

Two final guest questions. One is from my buddy Paul Hermann, who’s a huge fan and said, “Oh, really, you’re interviewing The Sheepdogs tomorrow? That’s fantastic. I’m fixing an ambulance.”

Ewan: That’s honourable work.

Paul wanted to know if you will be returning to The Kee to Bala… they miss you in cottage country.

Ryan: Yeah… We had a pretty good run, pre-pandemic, where we played every year for eight years or something like that. It didn’t really work into plans this summer but I have a feeling we’ll find ourselves back there.

And the final question is from his 12 year old son, Rod, who plays guitar and lives up near Jimmy Bowskill… ready? Where did you get the name Sheepdogs.

Ewan: Classic question. [laughs] It came to me in a dream

WORDS & INTERVIEW: DAVID GANHÃO

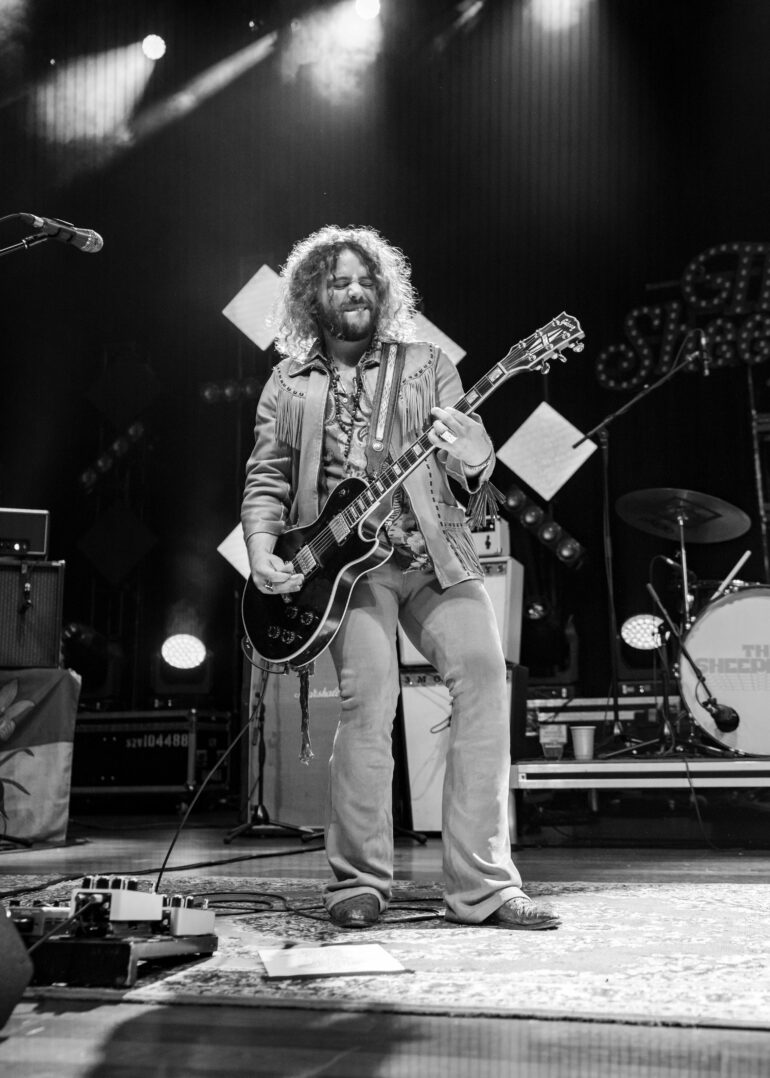

PHOTOS: MICHEAL NEAL